Jon Lord

Jon Lord, born in 1941 in Leicester, England, is a distinguished musician and composer who became famous when he and other members formed the rock band Deep Purple towards the end of the Sixties in London. He was their keyboard player for more than three decades, and only left Deep Purple in 2002 when he decided to dedicate more time to his solo projects and composing work. Jon Lord has made a big contribution to music history. His ‘Concerto for Group and Orchestra’, first played together with Deep Purple and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in the Royal Albert Hall in London in 1969, was very well received and initiated a change of attitude in both classical and rock musicians. Jon Lord has always tried to bring different music styles together: blues, jazz, and classic but also hard rock. Jon Lord talked to Xecutives.net chief editor Christian Dueblin about his music career, solo projects, compositions for Frida, the ABBA singer, as well as generally about the music business and his love for Switzerland, especially Zermatt. Read this interview with this distinguished gentleman from England, who is most certainly a living musical legend, and learn more about the Sixties and Seventies music scene and how it has developed up to the present.

Dueblin: Jon, it seems that there is something special about Switzerland that has brought you back many times over the last few decades. How did it come about that you´ve spent so much time in Switzerland, especially in Zermatt, a village in the middle of the Swiss Alps, surrounded by rocks, mountains and snow?

Jon Lord: There was a young ex-marine from the USA with a rich wife who tapped into the Zeitgeist of Swiss ski resorts in the early Sixties. He realized that English people who stayed in Switzerland at that time were quite traditional. All those big hotels were very good for elderly tourists and family holidays, but not for young people at that time coming from England. He bought the Hotel de la Poste and put three restaurants into this hotel. It was not a five star hotel, more of a three star. The rooms were quite functional. They were all clean and funky, but they still weren’t five star. Downstairs was a snack bar, called The Brown Cow, which is still one of the best meeting points here in Zermatt. You can eat sandwiches and meet your friends. Underneath was a disco. Its name was The Broken Ski. We just called it ‘The Broken’. So when I first came here in December 1971, a friend of mine told me I had to see this Hotel de la Poste. I arrived just before Christmas in the middle of a snowstorm. It was still the old station with lots of wood back then when I arrived. The station area was very old and traditional. There were lots of horse-taxis and only a handful of electro-cars. The horses were standing in the square, and I walked into a picture postcard. I came up the Bahnhofstrasse and went into that crazy hotel. It attracted me from the very first moment.

Dueblin: But how did you become aware of Zermatt in particular? There were other places such as Montreux, where you stayed at that time with Deep Purple, or Lucerne, Gstaad or Interlaken; they all have a lot of English and American tourists. Why Zermatt and not one of those famous places?

Jon Lord: Well, I was 30 years old and at that time I had never even considered skiing. But a friend of mine told me about Zermatt and this dynamic and fancy hotel. It was Tony Ashton, an English piano player and songwriter. He had played in the Hotel de la Poste. They had a bar band in the back bar. It was a famous place in music circles. In those years we had lots of jam sessions and a lot of famous people used to play at those sessions in Zermatt. Tony said after our record ‘Machine Head’ which we recorded in Montreux I should come to Zermatt. That was what I did almost 40 years ago.

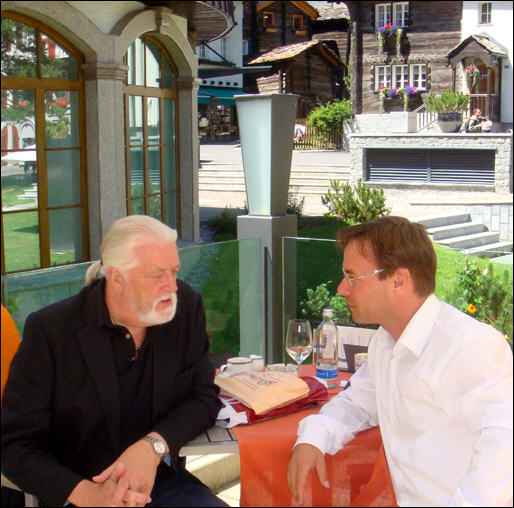

Jon Lord and Christian Dueblin in Zermatt, Switzerland

Dueblin: You were in Montreux just before you came to Zermatt to record the Deep Purple Album ‘Machine Head’ in a mobile studio lent by the Rolling Stones. Was this the first time you were in Switzerland? And how do you remember that time when the Casino in Montreux burnt down and almost destroyed your plans to record an album?

Jon Lord: The reason we were in Montreux was that we played in Switzerland and as you said, we wanted to record a new album. Claude Nobs, who ran the Montreux Jazz Festival, asked us to come over to Switzerland. We had met him a year before when we played at his festival. We were talking to him about recording with a mobile unit from the Rolling Stones. He said that he would be able to find a place to record the album. This was the Casino, and there was only one last concert before it was free for our recording. It was a concert with Frank Zappa; the last concert of the season. Then it would be closed during the winter season.

Dueblin: Then this terrible accident happened which you describe in the famous Deep Purple song ‘Smoke on the Water’. Claude Nobs is apparently ‘Funky Claude’, mentioned in the lyrics of that legendary song. What happened back then in 1971?

Jon Lord: Somebody fired a flare into the ceiling and the Casino started to burn down. Nobody is quite sure what really happened. But I met an American some days ago. He said that a friend of his was the guy who fired a flare into the ceiling. That is quite interesting so many years after this accident…

Dueblin: … and this might provoke an investigation and could lead to insurance problems…

Jon Lord: (Laughs) You are right, I am sure that Claude would like to sue him! I told that guy that anybody could say that they knew the guy who fired the flare. But he absolutely swore that he had known that guy. In the song it says “But some stupid with a flare gun burned the place to the ground”. It was an idiotic thing to do! Two things happened to me after that. We had got the inspiration for the song ‘Smoke on the Water’ and it was my first trip to Zermatt.

Dueblin: It is probably not clear to everyone in Switzerland, especially people who do not know a lot about the music business, but Claude Nobs is very famous and influential. As a professional musician who is linked to all festivals and famous people in the business – how would you describe Claude Nobs?

Jon Lord: He is ‘Mister Montreux’. He changed the fortunes of that town. It was famous for hotels and holidays, a sleepy and nice lakeside town like many others. Claude invented the festival and changed face of music. What he was able to do was to mix jazz and blues and rock, occasionally even with slightly classical music. You are quite right; he is a quite important but also a shy and generous-hearted man. In the middle of having the Casino burned down, he still managed to find us a place to record our album. In the midst of all his problems there, he found the time to manage our problem. He finally organised the Grand Hotel in Montreux, which we used for our recording while it was closed during the wintertime. We set up in there. He has been a good friend to Deep Purple, but also to me personally. I enjoy his company very much. He loves music. He eats music, sleeps music and breathes music and he plays a wonderful mouth organ.

Dueblin: You are used to being in Zermatt quite often. But what is it besides your passion for skiing that keeps bringing you here to the Swiss Alps over so many decades?

Jon Lord: I cannot count the times I have been here. But it is probably more than 300 times (laughs). Look around, it is such a great place, all those rocks, the snow and the blue sky. It is still this picture postcard that I like, and into which I walked almost 40 years ago. It appealed to me immediately. I fell in love with skiing and became quite a good skier. A good recreational skier, I would say. This is the story behind my love of Zermatt. I have always felt very much a part of this place. People know me, but whoever who you are, even if you are the king of the world, they would just leave you alone.

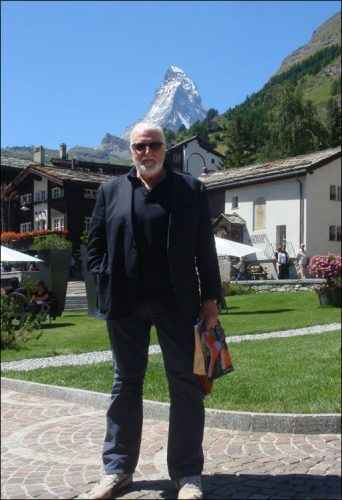

Jon Lord in Zermatt © Christian Dueblin

Dueblin: How would you personally describe the Swiss people?

Jon Lord: Swiss people are very polite. They are very aware of your personal space. That is what they value themselves. It seems to me that Swiss people are quite private people. I like that about the Swiss. I really love this country. I am more of a mountain person. I like the mountains much more than I like the sea. Maybe in a previous life I was a Bergführer.

Dueblin: Jon, you are a living legend in the music business and you yourself helped write musical history, not only with Deep Purple but also with your many solo projects. You contributed a lot to rock music, but especially brought together classical and rock music. You met some fabulous guys like Ron Wood’s brother, Art Wood, George Harrison, Tony Ashton and Andy Summers from ‘The Police’. Could you give us an idea of what was going on then in the mid-sixties in London where you used to live and play with bands and at the time when you brought Deep Purple together?

Jon Lord: Well, the music business in London in the mid-sixties was almost like a club. Pretty much everybody knew everybody else. Nowadays, the number of young musicians and people who want to become famous is much larger. Some believe that the music world is the quickest route to getting famous. They are very quickly disappointed. There are two reasons: one, it is not that easy to become famous and two, if this is the only thing they want; they do not have what it takes to be famous. If all you want is to be well-known, you won’t have the strength required to get there. You have to be exceptional in what you do and you need belief and endurance in your work. Finally, you have to be at the right place at the right time. It was very different when we started. What the Beatles did for us in the music business should not be forgotten. They really opened things up. They made it okay to experiment and to dare to be different rather than to just produce the standard pop music the early sixties management wanted. They produced the effect that the record companies became part of the process for musicians and became entrepreneurial. They were actively involved in searching out talents and not only in the search for the bottom line and the dollar at the end of the balance sheet. They really were interested in the music.

Dueblin: You say the record companies played a certain role as mentors with regard to some young musicians who wanted to discover new ways into their music.

Jon Lord: Absolutely! They had a definite mentor role. For example, Deep Purple’s first recording contract was for five albums. It was not for a huge amount of money, but we knew that we would make five records. The record company was investing in a bunch of young men who they thought had a certain something. They were investing in the likelihood that they would improve and discover more about themselves and therefore make better music.

Dueblin: Your first investors thought that you would just bang a pop band together. But what you and your colleagues wanted to create was a real rock band.

Jon Lord: (Laughs) Yes, they really thought that they would get a pop band, but then after three albums which became harder and harder then they got ‘Deep Purple in Rock’ in 1969/1970 which was the record that in my opinion defined hard rock. The time of ‘Child In Time’ and ‘Speed King’ was the defining moment in Deep Purple’s life, when Ian Gillan and Roger Glover joined the band. Music was changing back then. It was a very exciting time back in the sixties. Music business was a village and in a sort of way, you knew everybody. There were no rules. Nobody said music has to be this way or that.

Dueblin: You are still in the music business, which you observe closely and you have also assumed a mentoring role for younger talents. In your opinion, what do you think is happening in the music business at the present time? Are you a little bit disillusioned?

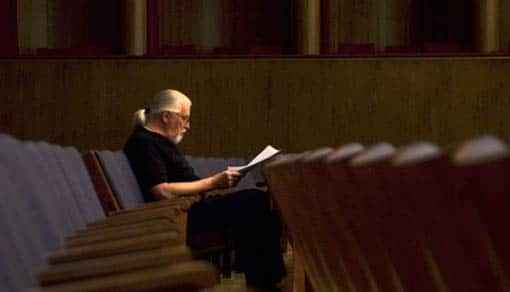

Jon Lord at the Hammond, DEEP PURPLE – The Albert Tour, Germany, October 2000 (c) Klaus Porzia

Jon Lord: Oh yes, but when you get my age you get disillusioned with a lot of things. Things change and especially one’s recognition. The first thing that happened, the record business stopped being entrepreneurial and became capitalistic. Music was considered a cash cow, a cash machine. As a result, it stopped investing in the future and potential artists. All it wanted was an instant artist like a kind of ‘instant coffee’. Music and fashion started to shake hands a lot more than before. But there is hope: I have seen some really wonderful musicians come through this period in the last 2 or 3 years. They are not becoming famous because of the music industry but in spite of it. But also the digital revolution changed everything once and forever. This was a Pandora’s Box. Once music is digitised, you cannot stop it being given away. File sharing, downloading, pirating – all that changed everything. The music business did not see this development coming. They were told, but they thought, ‘it won’t happen’. The record industry lost the massive profits they had and meanwhile, music has become a kind of ‘cottage industry’. Young musicians write music at home, and record it at home. Something happened a few years ago. I cannot exactly say what – I am not such a keen observer – I just know that it is going on. Talents are starting to shine through. “The X Factor’ and the talent programmes have produced some absolutely brilliant musicians.

Dueblin: Like Paul Potts…

Jon Lord: Yes exactly, but also Leona Lewis. What an incredible voice and what an astonishing singer she is. She was the best thing on it. It proves that the talent show system, cruel as it may be – and it is cruel – cannot stop them. The shows are a spectator sport. But when they produce people like Leona Lewis they are fascinating.

Dueblin: Do you think that audiences in the last couple of years have become more interested in high quality? Do you notice any changes within the audiences?

Jon Lord: Yes, I notice a change. People are more discerning. Young people are very ‘savvy’, very knowledgeable. When my daughter was 13 she knew almost as much about pop music as I did. This is because of the media and MTV.

Dueblin: In 1969 you initiated that famous concert together with Deep Purple and the London Philharmonic Orchestra in the Royal Albert Hall. You were the first to put a famous Rock band together with a philharmonic orchestra. This seems to me, looking back to the sixties, like a enormous experiment and I suppose you ran a great deal of risk back then, composing and developing a completely new kind of music.

Jon Lord: (Laughs) It was slightly crazy! I can tell you why I did it. The young man, in fact, the young boy, I was then, was introduced to classical music by his father. It was not so much that my father was a great lover of classical music, but he thought it was important that I should be exposed to it. I had learned to play the piano at the age of 5 or 6 and I bought classical discs with my pocket money. Hearing Rock’n Roll did not drive my other music out. It just came and sat beside it and I loved both. That has defined my musical life. I am a fan of music and not a fan of labels.

Dueblin: For some years you went to an acting school. That surprised me. What was it you were looking for in an acting school, as a potentially talented musician?

Jon Lord: I was looking to escape my home town. I realised that I would die inside, if I stayed in Leicester. Don’t get me wrong, I did not feel that there was some great mission in me and that I would lead the world. My father, he is my hero in my life, but he worked in manufacturing all his life. He lived a very warm and happy life. Besides the factory job he had his music. That and his family is what he found outside the factory. But I could easily see that if I stayed in Leicester I would end up working in a factory or in an office. I became aware when I was eighteen or nineteen that this was not for me. That is why I went to London and entered the drama school.

Dueblin: What you say is very interesting, because I think there are so many people who do not take on the risk of a new start. They probably also have the skills and the talent to do other things rather than what they finally do their whole life long.

Jon Lord: That is a very good point. But in a way, it is a natural selection process, a kind of Darwinism, but rather Darwinism of the mind rather than of the body. I mean, what is the famous phrase: ‘Many try but many fail’ – but some succeed! I think that is the nature of every intellectual pursuit. The great thing about music is that it is not just an intellectual pursuit, it is an emotional pursuit. I love the combination of the need to understand the technicality of music and the absolute emotional and sensual content of it. It must come from my heart to your heart and not only from my mind to your mind. That is what attracts me to music. The older I get the more annoyed I am that I did not grasp that earlier. I stopped writing for some reason in 1976. I lost my ‘mojo’ as they say. The muse had gone. Maybe it just sat behind me and said, ‘I’m here!’ and I did not hear her.

Jon Lord

Dueblin: The acceptance of your Concerto in the Royal Albert Hall with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London was fantastic among the younger audience and it was definitely a big milestone in music history. The rock business accepted the coming together of the two music styles much better than the classical side did. The classical side would not have touched such a thing at that time.

Jon Lord: It was a fight against the brick wall. If it not had been for the help of Malcolm Arnold who was a highly respected composer and conductor, respected in the classical world, it would not have been possible. He stood in front of me, protecting me from the anger some people in the classical world felt.

Dueblin: But also Malcolm Arnold, a very well respected musician ran a great risk, supporting such an idea that could have failed. What made him believe so strongly that it would not fail?

Jon Lord: He was very brave, and liked my score when I showed it to him. He liked the music. He said it would work. We started off in the Royal Albert Hall and he let me do all the talking. He wanted me to explain what I wanted. Of course I was able to convince people. It was musically valid. It was well crafted, but it was also difficult to play for the orchestra.

Dueblin: Was everything strictly set, or did you let the orchestra improvise?

Jon Lord: Not in that piece. Everything was written out. I did another piece a year later, the “Gemini Suite”, in which the orchestra is encouraged in one or two places to improvise. But it is not terribly successful. It is not that the classical people did not have the skill, but they did not have the tradition of improvising. The Rock Band was based on improvisation. That was 75% of what we did on stages. By improvising we discovered more about ourselves. Some people came to us after a concert and said: You remember that thing you just played, it was great! The next day we would probably have made a song out of it. It was the key to what we did.

Dueblin: To make the link between classical and rock music you needed not only your vision and your composing skills but also an adequate instrument. You are definitely the musician who made the Hammond Organ famous in rock music. Was the Hammond Organ a link or bridge to classical music, the thing that kept everything together?

Jon Lord: That is a good question and I suppose in a way it was. To me the Hammond was more of a bridge between jazz and rock. When I first heard the Hammond Organ I was not playing rock music. I was at drama school back then and heard Jimmy Smith playing the Hammond Organ.

Dueblin: Wasn’t there probably a kind of misunderstanding on the classical side? They wanted music with a philosophical and classical background. You wanted to do something creative that brought classic and rock together and you wanted to make people happy.

Jon Lord: Absolutely! The thing is, once you start to compose music for a large symphony orchestra, if you are going to give it the character of a symphony orchestra, and not just, like I said before, and not make it sound like a giant backing band, or like a big synthesiser, the character is what you just described. The orchestra has to have this philosophical and intellectual backup to it. It has to – if not it is just a synthesiser. Of course I have that on board when I am writing for the orchestra. That was the wonderful puzzle I had to solve, the style and the feel of a rock band and an orchestra.

Dueblin: What is your approach to composing? Is this a process of try and try again? Or is it already clear in your mind what you are going to put down on paper?Or is it more a kind of evolution looking for the right keys and harmonies on the piano?

Jon Lord: Again, a very good question, and you almost answered it yourself. It is both. That is the fascinating process. Sometimes composing is purely emotional. I am sitting at the piano and an idea just happens. Other times a fragment or a little piece or something happens. This must not be in front of a piano. It can happen here, drinking a coffee or reading a book. I just float in and write it down and take it home and work on it again. This is why I love the process. I am not aware where it comes from. This is the magical thing about the human mind. You can conceive something and hear it in your head. Then you put down black dots on a white paper and some weeks later you play it together with an orchestra. That is very satisfying.

Jon Lord

Dueblin: One of my favourite compositions by you is ‘Sarabande’. I hear a little bit of Dave Brubeck in this composition. It is also linked to baroque music, very peaceful and steady. What emotion did you experience that allowed you to make such a composition? Besides, it is perfect film music!

Jon Lord: The interesting thing about ‘Sarabande’ is about losing my ‘mojo’. It was a big thing. It took it all out of me. I loved that project. It is a combination of jazz, classic and rock. It has a smile on its face and it is not over-serious. I used to play one or two pieces out of it for my solo concerts. But I did not play the entire suite in full. I asked Andy Summers from The Police, if he would like to play it again. But that is for the future. It was written mostly in ´74 and ´75, when I was living in California. I realised that if I wanted to do any work, I had to move from Los Angeles. I found something very peaceful up there in Malibu. It was ‘Sarabande’. All the themes came quickly in that environment with that beautiful outlook on the sea.

Dueblin: Some years ago you went on stage with Frida, the singer of ABBA. How did you come to write your song ‘The Sun Will Shine Again’ interpreted by Frida?

Jon Lord: I met her here in Zermatt. We became friends. She had just lost her husband. It was a huge shock and she was very lonely and in pain. That is when we became friends. My wife and Frida became just like sisters. Two or three years later I was going to make a record. “Beyond the Notes” is the title of the album. I had remembered having said something to Frida when she came out of that difficult time. I said something like: “The great thing about life is that eventually after a sad thing the sun will shine again.” I was playing the piano and I suddenly had that tune in my head. Just those words “The Sun Will Shine Again” fitted into that tune. So I wrote on the paper and went to my friend Sam Brown. She did the lyrics. I asked Frida if she would like to sing it for my record. She said she would do it if she would like it. I made a demo, showed it to her and she was very touched and liked it. I like the words very much, very thoughtful, beautiful and emotional words. Sam Brown did a perfect job, and Frida has this wonderful mezzo-soprano voice that goes quite deep. It is a very unusual voice and very attractive.

Dueblin: I have recently heard your song ‘Menorca Blue’. Something is different in that song. It seems to me that it goes much deeper than your other music. How did you come to compose that song with that melancholy note?

Jon Lord: That is interesting. That is what I love about music. It is different things to different people. But you are right; I was in a very blue place on that island. I was actually on the island in wintertime and it was a beautiful cold day. There was nobody there. I felt this melancholy. I did not have a piano but I could feel the shape of the keys under my hand. Then I wrote the string quartet opening for it. I am very proud of it. I am glad you like it. Everybody feels down sometimes and the wonderful thing in being a musician is that you can express it. It helps you to get out of it. Sometimes in fact, when I am writing a lot, I write more slow melancholic music than up-tempo music. Slow music is very often easier to compose than up-tempo music. I don’t know what it is, but it is wonderful to be able to draw such music out of our inner selves.

Jon Lord & Christian Dueblin-in Zermatt, Switzerland

Dueblin: What are your next projects? Will we also be able to hear your concerts in Switzerland?

Jon Lord: My agency and my management are working on an offer to come to Switzerland at the end of January and into February 2010. I think three concerts are planned with an orchestra playing some of my orchestral pieces. I played earlier this year in Zurich and Lucerne. I imagine that we will go back to those places. I am going to Russia for the first time with an orchestra. I have been there two or three times with Deep Purple. I am also going to Bulgaria and again to Germany. I also plan to give concerts in Scandinavia and Italy and in other places in Europe.

I came up to Zermatt to do some composition work. Although I have a music room and refuge at home, it is much better to be here to work. Up here, I do not have a phone in my apartment and can work and walk surrounded by this beautiful landscape.

Dueblin: Dear Jon, thank you very much for giving your time for this interview. I wish you much success for your concerts, and lots of inspiration for your compositions here in Switzerland.

______________________________

Links

– Jon Lord – The official Website

– Jon Lord on Wikipedia

More Interviews with musicians:

- Richard Clayderman about “Ballade pour Adeline”, his approach to music and his personal feelings about interpretations

- Chi Coltrane about her comeback, about other music legends and the secrets of the music business

- Hazy Osterwald about the beginnings of his career, his love of jazz and the changes in music during and after World War II

- Nicki Parrott about her love for Jazz, her career, music legend Les Paul and the significance of musical mentors for young talents

- Dick Hyman about playing the piano, jazz and life

- Giovanni Antonini about his musical career, authentic performance practice and his approach to conducting